Happy New Year!

What follows is the prologue from a fantasy novel I’ve been chipping away at since the pandemic. I’m currently calling it The White Winged Dove, but that’s just a little inside joke with myself because the protagonist is on the edge of seventeen. I still don’t know what the real title is after these years. It has been Torchlit Bones, The Hidden People, and for a bit it was All The Bears and Snakes In The Woods.

I hope you enjoy it.

November ‘20 - In the Oldest City

Japeth Grady operated as a street preacher in The Oldest City, which was the capital of The Oldest Country.

He commanded the attention of the streets with an operatic charisma, spellbinding the dupes with candles and bells and flashes of magic powders from his sleeve while his three sons moved unnoticed through the crowd, picking the tithe from the sinner’s pockets.

They did well until Grady’s debts caught up with him in the middle of the night, as had happened before, in other cities. An angry pounding at the door, a half-dressed flight across moonlit rooftops to the city gates, and then out into the wild, the dark and the rain. They barely had time to gather their belongings and props, and disastrously left the purse containing their entire fortune of coin on the nightstand, rendering them destitute. Grady was roaring drunk at the indignity of it all when they were out on the road, having grabbed a jug of poteen although he had neither coat nor hat. They were soaked and filthy and miserable and still pursued, and they walked all night and day, ducking into the trees whenever they heard hooves or voices, until they couldn’t walk any more and crept under a hedge, the sons weeping, their father insensible with drink. When the sun woke them they were without even a street beneath them, so they could hardly call themselves street preachers. They were under a hedge, so they were hedge preachers now, at best.

They went north, because no one knew them in the North, and the air grew colder as they walked. When they reached the frigid coast they set off along the beach toward a desolate sunrise.

They had walked for days before they spied a fisherman’s settlement over a bluff, and before approaching they stopped to clean themselves up as best they could. Seamus, the oldest boy, smoothed out his father’s flea-ridden tabard and matted beard, then slapped both of the old man’s cheeks until his eyes were open wide. Japeth growled and wailed, preparing for his performance. The younger sons lit their last stick of candle as they walked into the settlement, singing hymns in loud voices, and the fishermen came out to look at them.

It was said that the difference between The Oldest City and The Oldest Country was a thousand years, but the Gradys had never been so far north, and what they saw in the town shocked them. The townsfolk seemed as if they had never met a stranger. If viewed uncharitably, they also seemed to have recently climbed out of the freezing ocean and begun to walk on two legs. Men, women, and children all shivered in tattered, rough spun wool, and there were weeping sores on the faces in the crowd, missing eyes and limbs. It was clear to the Gradys that there was little money to be had in this place, and clearer still when a fat man with a sheriff’s star on his blouse walked up in front of Japeth and spat in the mud at his feet.

“Nae priests here, nar gods neither,” he said, his rustic accent so acute as to be barely comprehensible to the urbanite Gradys. Then he produced a wooden baton from his belt, and pointed with it at a sign that was hung there in the street, and which read the same in a barely legible scrawl:

NAE PRIESTS HERE,

NAR GODS NEITHER

Japeth’s voice rang out: “Do not mistake us for common mummers, brothers! We bring the word, and we bring hope—”

The baton flashed across Japeth’s face, and he fell to his knees in the mud, cursing through a bloody mouth.

“And daren’t ye says aught again, neither,” said the sheriff.

“We’re going, we’re going,” said young Seamus, scrambling to gather up his father.

The sheriff followed until they were at the town’s limit, where he spoke to them again. There must have been some touch of tenderness in him, at least when he looked at the visibly starving boys.

“Easterly fer a two-day,” he told them. “Ye shall spy the vastly mon-astery ‘pon the bluff there. They may feed ye, if ye earnestly keep. Nae sass talk, nar horseshit. Noses clean. Sank-cherry.”

The sheriff pointed at the horizon with his baton. The Gradys barely understood what he had said, but slouched away down the beach anyway. He stood and watched until they were over the horizon.

They walked for a day and a night and then another day, then they saw it up on a bluff facing the frigid gray beach: a great stone house, large enough to sleep fifty at least, with cheerful woodsmoke coming from six chimneys. They could see a dormitory, and a chapel with stained-glass windows, and a brewhouse and bakehouse and buttery, and oh, there must have been so much beer, and wine, and bread, and money. They cleaned themselves up again, but not quite so much this time because they wanted to appear poor and hungry, which of course they could hardly help by that point, especially with Japeth’s newly broken front teeth.

The old abbot who met them at the gate had a tired face.

“Men of the cloth, we are!” Japeth called out. “We preach the Sky Father to those what will listen!”

The abbot nodded with grim professionalism.

“That’s good enough talk,” he said.

The abbot showed the Gradys to a stable and told them to muck it out. If they did well there would be broth later. Seamus and his brothers worked at it all day while Japeth slept in the haypile, and when the abbot came back he sighed and nodded and took them to the dining room: a great hall of polished wood with tapestries on the walls, where cheerful monks fed them broth, bread, and beer. Their hands trembled, and eating made them all a little sick after all the walking and privation, but they spent the night safe behind the stone walls of the stable, and they didn’t even steal anything because everything that they could want had been given to them for free, or at least for work that was easier than stealing by half at least. A few weeks later they had forgotten the evangelical life, and now they were monks, in coarse woolen robes, their hair cut into tonsures.

The monastery’s brewmaster took a shine to young Seamus, and found that the boy had a talent for the patient work of brewing beer. Working among the kegs was the first time in his life when Seamus was not in the same room with his father and brothers for an entire day, and the quiet and lack of worry was an unfamiliar balm for his mind after the constant anxiety of his father’s drunken presence, the weight of his need, the ever-present danger that surrounded him. His brothers were safe and cared for, and his father was out of trouble and out of sight. Life in the monastery was a profound comfort, especially in the brewery, with its warm rooms full of soft light, and the calm tutelage of the brewmaster.

You may think of a monastery as solemn, but this was a jolly place, where days were spent drinking beer, roasting potatoes, reading books, and tending to the prolific vegetable gardens. They shot the excellent wild chickens that ran through the aspen forest behind the monastery, and pulled eels from the creek which ran through it. There was a calligrapher among them who spent each day adding an enormous single letter to a gilt-edged tome the size of a barn door. There were philosophers translating scrolls and clay tablets in ancient languages. There were brewers and vintners, and much fussing over the quality of their products, and selling them to the locals, and drinking copious amounts of them.

There were no women around, which most of the monks didn’t seem to mind, but some kept a set of non-ecclesiastical garb hidden for trips to the nearby town, and what they did there was their own business. The Gradys never snuck into town, or left the grounds for any reason. They were too comfortable to risk exposure, and the brothers were young and innocent, besides. Like their father, they had little use for women, and in their lives they had hardly known any. For Seamus their own mother was a faded memory, and to his brothers she was nothing at all.

When Seamus had gained the trust of the brewmaster he was sent to town on occasional business; buying supplies or selling excess stock. On one such mission he became aware of the daughter of the proprietor of the local inn. Her name was Julia, and she was older than he was and strikingly tall, too tall for the taste of most of the men in town. But Seamus had also grown tall, and he admired the sweep of her long limbs as she worked, as well as her cool, green-eyed gaze in response to his own.

Whenever Seamus went to town he would go to the inn after his work was done, to order an ale from Julia, and then to sit and watch quietly as she did her work. They watched one another, in fact, he in his tonsure and habit, she in her foam-tinted shift. He thought often of what to say to her, but never managed a word other than to thank her for the ale. Julia noticed the monk staring at her, week after week, and eventually confronted him.

“What’re ye lookin’ at?” she asked.

He couldn’t think of what to say.

“Oy,” she said. “Can ye speak?”

“I can,” he said.

“You in love with me or what?”

Drinkers at the bar laughed, and Seamus went crimson, nearly choked on the ale in his mouth.

“Guess so, then,” she said. “Were ye never gonna talk to me?”

He searched his soul for a long moment. He went all the way down to the bottom of himself, and when he came back up to the top he had found nothing, not a single word that he was not terrified to say. He stared mute, jaw hanging dumbly.

“Waste of me time,” Julia snorted. “Feller like you’ll get a woman killed. Come back when you’re a man.”

And with that she went off back to work, and the drinkers roared as Seamus crept out of the inn. After that he would avoid her eyes when he made deliveries, and would never tarry afterward.

Seamus and his brothers all learned to read at the monastery, and even to write a bit. The younger boys worked as pages in the chapel, tending to the candlesticks and bells as they had in their previous employment, and calling the monks to prayer. Their father spent most of the day in bed, snoring and drunk, passed out naked, bare ass skyward. To the monks he was the sort of fool who approaches innocence — so purely ignorant of virtue that by his lack of guile he approached something adjacent to holiness. So they let him be, and brought him the things that he asked for without complaint. Seamus had never dared to picture such a peaceful and contented life. He saw the rest of his years spooling out in contentment in the monastery by the Northern Sea, with little to trouble him other than his preoccupation with the innkeeper’s daughter.

So later, in retrospect, as he was being led away by the Icekind raiders who had just looted and burned the monastery, and killed or enslaved most of his fellow monks, he could not understand how it had ever existed: this unguarded cache left out in the open on the naked coastline. Rich men and nobles had donated land and the money to build all of this, and then the Icekind had simply come to take it.

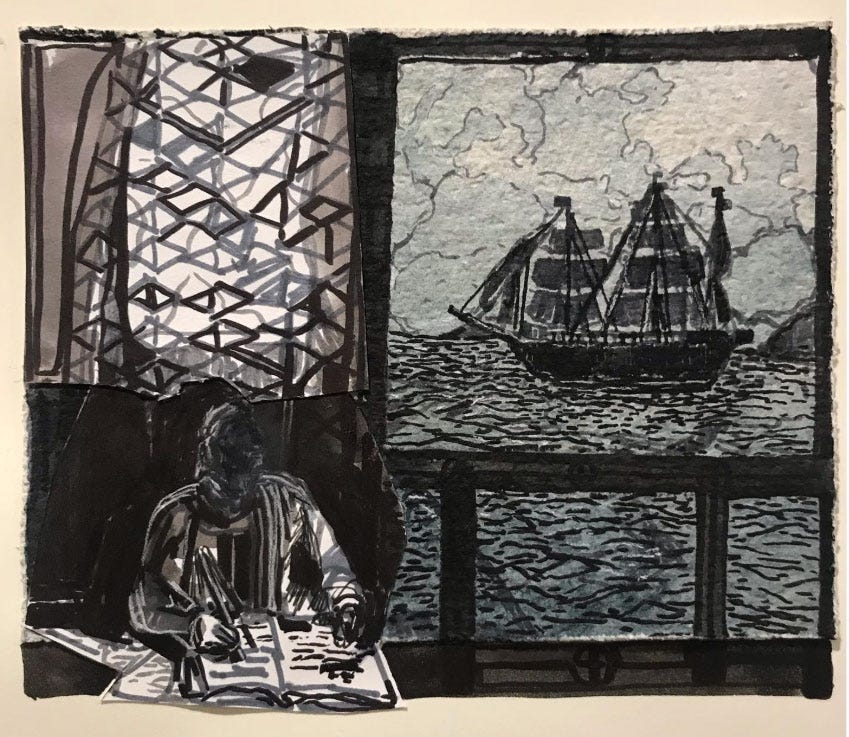

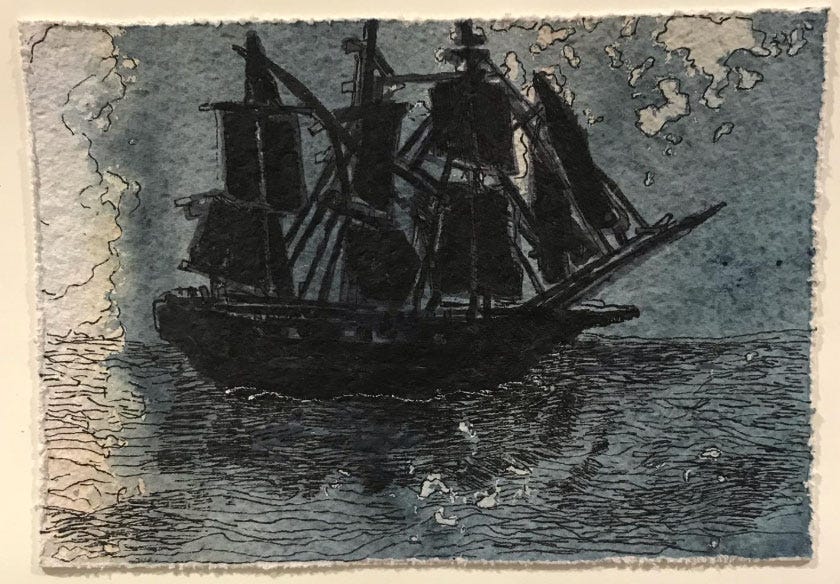

That morning asleep in bed, Seamus thought he heard screaming. He lay there for a cozy moment, then all the alarm bells went off, and he ran to the window and saw the longship anchored off the rocky shore, just past where the frigid breakers tumbled into the channel carved in the jagged black rock. Two dozen raiders were wading ashore brandishing broad axes. They were an anachronism: a nightmare from the past, suddenly returned without explanation.

The monks had a sergeant-at-arms, but an argument could not resolve which one of them currently held the role. They had an armory full of expensive weapons: never-fired muskets beside untouched suits of armor, dull swords and dusty shields, a ballista that no one knew how to operate. Most of the brothers were too fat to wear the armor, and none had ever raised a weapon in anger. The youngest and least terrified among them geared up as best they could and formed themselves into something like a line in the courtyard. Seamus barred the door to Japeth’s room, then took up a shield and spear and went out with the others for a short, bloody skirmish.

By the end of the day Japeth was dead, having mercifully slept through his own murder. The Icekind slew all the monks who were too weak or old to be valuable as chattel, and gathered the rest up, along with all the gold and brass and silks. Seamus found himself hog-tied and struggling to breathe, face down in two inches of ice water in the bottom of the longship. The ruined monastery belched black smoke over the gunnels.

His brothers were not in the boat with him, but soon he realized that Julia, the innkeeper’s daughter, was. A purple bruise shined on her right eye socket, and she screamed bloody murder at the raiders until one of them tore a long rag from her skirts and gagged her with it. She noticed Seamus as they sailed off, and they shared a mute moment of recognition. She stared at him for the entirety of the voyage, and her eyes were a mute accusation of cowardice.

It took a day and a night to reach the nation of the Icekind: an island of stunted birches, where the air reeked of sulfur from a series of active volcanoes. Upon landing, the raiding party sold off all the silver candlesticks and gilt-edged books in a muddy port town, along with the incense, tapestries, peridots, agates, and slaves. No one bought Seamus, who was pudgy from easy living and buffoonish to the Icekind in his tonsure.

As the market day ended the newly-flush raiders were drunk and getting drunker, and amused themselves by forcing their unsold captives against one another in pit fights. They roared with laughter, betting on the leftover boys, who were given spears and shields and pushed two-by-two into a pit rimed with icy slush. Seamus found himself across from a shivering lad in nothing but mud-streaked breeches, rendered nearly subhuman by hunger and rage. When the boy screamed and leapt forward to stab at him, Seamus raised his wooden shield and instinctively planted the butt of his spear in the mud behind him, steadying the sharp tip which impaled the kid in his skinny belly, causing him to crumple, transfixed and howling furiously as he bled out. Seamus vomited as the boy died, but the Icekind cheered his valor.

They gave him a bowl of porridge and a goblet of black beer. He spent a paranoid night laying awake in a locked barn with the other surviving boys. He assumed he would have to defend himself, but everyone was crushed and exhausted, weeping softly, calling out for dead mothers in their sleep.

As the weeks passed the Icekind gave Seamus chores to do: repairing fortifications, peeling rotten tubers. They taught him to passably speak their language, and to row, and march, and wield their preferred weapons: the broadaxe, the bow, the spear and the sword. Some had muskets, but they were like men from a distant era, trusting steel over all. They taught him how to wield their steel, and to join up with his compatriots in a proper shield wall.

To the surprise of no one more than Seamus himself, he proved to have a talent for this work, as he had at brewing. His heart had been hardened by the loss of his family, and the loss of his content life in the monastery. His body grew lean and hard from work and training. He found himself not only capable of violence, but in fact proficient with it.

And so now he was Icekind. He received the blue tattoos across his arms and face that would mark him for life: testaments to valor and bloodlust, bestowed in painful ritualistic ceremonies by jabbering shamans tripping on magical herbs. He would have been unrecognizable to anyone from his life at the monastery, or the Oldest City, and indeed, none of his former countrymen could tell that he wasn’t naturally born to the Icekind. He killed those that he was told to kill, and was known as someone who could be trusted in a fight, and feared if double-crossed.

The campaign season that year was full of fierce battles, both on land and at sea. Seamus was fourth spear in a longship company. They roved the coast, conducting profitable strikes against barely defended villages. His life became a constant whirlwind of violence. Every day he saw things that would ruin the lives of other men, and did things that most would never be able to forgive themselves for. He watched as berzerk raiders fell on muddy towns full of nothing, like packs of ravening wolves, killing for sport. He told himself that he had never had a choice, that he was a slave and an orphan, a man with nothing, doing what he had to do to survive.

But when everyone else was asleep, in the small hours, as he lay in his bunk in the longhouse full of snoring murderers, he knew that he did have a choice. He could walk away, and he needed to do so, or he would never recover himself. He made a quiet decision that night; one that he wouldn’t be able to act upon for some time.

He was wounded several times. He had a scar on his face from a rock thrown at him by a child, and he walked with a slight limp after being crushed by a dying horse. He also distinguished himself several times among the Icekind for his bravery and general competence. When the campaign season was at its end, the Jarl of the Icekind offered Seamus the reward of his choice.

Seamus asked for three things:

First, a boat. It should be a light craft, a skiff perhaps, that he could sail on his own in rough seas and deep water, without a crew.

Second: fifty golden crowns, a modest percentage of the loot he had personally given to the jarl as tribute over the course of the campaign season.

And finally he chose a wife: Julia, the innkeeper’s daughter he had known from town, and who had, as a result of her foul temper, been kept a field slave until that point. She lived alone in a mud hut, charged with plowing a turnip field and caring for a sty of pigs.

The jarl was surprised. He would have bestowed greater wealth on Seamus, and more beautiful and agreeable women, a dozen of them if he had asked. But the Jarl respected a man who knew what he wanted, and had more important matters to attend to, besides. He never suspected that Seamus would leave the raiding company, and would take his new bride and sail back to the Oldest Country in his new boat.

But that is what Seamus did.

He went to the farm where Julia was held, a crumpled bouquet of roses in hand. He described her to the overseer, who went to find her, and when she was before him, sulfurous in pig shit but radiant in her anger, he told her that she was now his wife. Her owner appeared to hem and haw, but Seamus held the deed that proved it, with the jarl’s signet ring impressed in its sealing wax.

Julia’s eyes were blank. She hadn’t seen Seamus in a long and hard year, pulling radishes from frozen earth, fending off drunks in the dark. This man was no longer the soft boy she had barely known in that previous life. He was huge and fearsome, and marked in nearly every inch of his flesh.

“Pack your things,” he told her.

“I have none,” she replied.

The man who owned Julia untied the cord from the metal stake that bound her, and handed it over to Seamus. They walked off, man and wife, Seamus holding the end of the cord still tied around Julia’s waist.

When they were out of sight among the scabrous birches he stopped and drew his dagger. She never flinched, her eyes hard as he brought up the blade to cut the cord from her waist.

Then she recognized him, suddenly: the monk from the inn was now the Icekind raider before her. She gasped.

“It’s ye,” she said.

“Aye,” he replied.

“So ye love me then, still?”

“Aye.”

He turned to go. She stood watching for a moment, and then set off after him, having nothing else in the world; no other option. She stayed a few paces behind, following him to the port town, where his tiny boat was moored. It was late at night, and a cold rain obscured them as they boarded the craft. She sat on the bench before him, watching as he prepared to take up the oars. Once the ropes were loose Seamus reached into his chainmail jersey to produce a leather purse. He handed it to her, and she looked inside and saw the gleam of gold.

“Fifty crowns of the Oldest Country,” Seamus said, pushing them away from the dock with an oar. When they reached the deep water he set up the sail and piloted the skiff across the Northern Sea.

They sailed past the ruins of the monastery, where ragpickers squatted in what had been the courtyard, a trail of greasy smoke rising from between the remains of the walls.

They kept sailing, and saw the nearby town where Julia had lived, also burned. They disembarked and walked quietly through the ruins, finding nothing of value, tears streaking both their faces.

Then they got back into the skiff, and continued along the shore until they reached the fishing village where, a lifetime ago, the sheriff had broken Japeth Grady’s teeth with his baton.

Astonishingly, the same sheriff was waiting on the beach when the skiff landed. He had seen the Icekind standard on Seamus’s sail, and had come out to do his job. The fishermen and their wives all stood gawking as the sheriff, older and fatter now, waited, armed with a pistol.

Seamus came up the beach unarmed, glowering with his tattooed face. The sheriff leveled his piece and fired it, but the shot went wide over Seamus’s shoulder, and Seamus reached the sheriff and punched him in the mouth, knocking him down. He took the Sheriff’s dropped pistol from the sand and tucked it into his belt.

“Owed ye that,” he said, before turning to address the crowd of fishermen.

“Any of ye lot want to buy a skiff and a gun?”

Seamus and Julia walked away from the village. The sun was rising behind them, and now there were one hundred crowns in their purse, enough to start a new life.

They went South, toward the Oldest City, and it grew warmer as they walked. Julia was startled by the modernity of the city and its worldly inhabitants. They rented two rooms in an inn in the rundown district near the docks, where Seamus left her for the day. He bought an old clapboard row house, which smelled of mold but was a good place for them to get started. He bought yeast and grain and other supplies, and wood and pig iron to make crude kegs, and he hung out a shingle that read:

DECENT BEER, CLEAN BREAD

He stayed in the back, working, his tattooed face out of sight. Julia stayed in the front. She sold the beer, and she baked bread for they who came. There was a clean room for Julia behind the taproom, with good light and a narrow bed and fireplace. Seamus slept in a pile of rushes in a stuffy garret above his workshop, and he slept there alone.

They were there for the better part of a year, and things changed between them over time. He had never touched her until one cold night in midwinter, after they ate a potato soup and reviewed the day’s receipts, when all the drunks had been chased out and the exterior doors were closed and locked. Afterward Seamus went up to his garret cell, and as he lay in the dark he heard her come up the stairs. She crossed the hallway to the room where he slept, and stood over him on the floor. She invited him to come down to her room. He had the horned hands of a soldier, but he was gentle with her.

From that night on they both slept in her narrow bed. She gave birth to a son, who they called William, and a year later she was pregnant again, and she told him that she knew that it was a girl. And now they were a proper family, and Seamus was a husband and a father.

The raid on the monastery turned out to be a historical and political turning point among the countries of the Old World, which had forgotten the threat of savage men from the Northern islands. Such raiders had not been seen on the coast for centuries, and Northerners had lapsed into a comfortable complacency. But the raid, devastatingly violent and expensive as it was, and all those which followed it as the Icekind grew bolder and roved along the Northern shores, turned out to be a clarion call. All the countries of the Old World mobilized, and the Oldest Country in particular, led by Aethelwulf, the young and charismatic scion of The Oldest Family, who had longed for a chance to show his mettle, and who led his countrymen against the Icekind. Soldiers and sailors were badly needed for the Prince’s war, and royally sanctioned gangs of thugs roamed the Oldest City, rooting out unwilling sailors and pressing them into service.

Seamus was tending bar when they came in. He wore long sleeves and a hood to cover his tattoos, but when the captain of the press gang ordered an ale and saw the blue octopus on his wrist, he grabbed Seamus’s arm held it down on the bar.

“What ship?” the captain asked.

Seamus growled. There was a brief fight, and Seamus knocked more than one man unconscious before he was taken down.

He woke up in the hold of a ship, his hands bound, a gag over his mouth. The lightless room was tightly packed with groaning men. Soon a chamberlain entered, flanked by royal lawyers and a group of armed bouncers, and read a proclamation to the men, all sworn then and there into the service of the Oldest Navy. They would be free of the service in ten years, should they survive and maintain their honor.

When Julia returned to the inn she found the doors open, drunks scrabbling around behind the bar, pulling at the taps.

“Them pressers took ‘im, mum,” called one old souse. “Make way to the port, ye may get a last glance.”

Julia swaddled William to her breast, and ran. Everyone in the Oldest City knew of the press gangs, and many weeping mothers and sons had come to the port that day to see their husbands and fathers for the last time. She couldn’t be without Seamus, and William couldn’t either. In the confusion on the dock Julia dove onto the shady deck and hid behind a stack of barrels. As the ship pulled away it began to rain. She made her way below decks, and it was too late now. She had made a hasty choice, and now she and William were bound to it.